M31, M32, M110 (The Andromeda Group of galaxies)

040: The Andromeda Group

At a distance of about 2.9 million light years, the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, is at the same time the nearest major galaxy to our own, and the most distant object readily visible to the naked eye. This photograph actually shows all three of the Messier Andromeda Group. M31 is of course the large galaxy. M32 appears as a bright circle at the upper left edge of M31, and M110 appears as the bright oval at lower center.

M31 is often considered a twin of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. Although they have similar structures, there are differences. The Milky Way has a total mass of about 800 billion suns, versus 350 billion to 400 billion suns for Andromeda. Also, Andromeda has something like twice the physical extent of the Milky Way, which means it is much less densely populated than the Milky Way.

Huge does not begin to describe the apparent size of Andromeda. If you told a non-astronomer there is an object in the night sky that makes the full moon look small, he’d think you were nuts. But at about six degrees long by two degrees wide, Andromeda is indeed that large. If we superimposed the full moon on this image, it’d be less than twice the major-axis diameter of M110 down there at bottom center. The reason most people are unaware of M31, of course, is because it’s much dimmer than the moon. But as Messier Objects go, it’s quite bright.

Andromeda has been known since ancient times, and almost certainly since prehistoric times. The first known reference to it was by the Persian astronomer al Sufi, who observed it as early as 905 and described and drew it in his Book of Fixed Stars. M31 was a well-known object before Messier added it to his list, although Messier was apparently unaware of most of the earlier reports. Messier first logged M31 (and M32) on August 3, 1764 as the first galaxy in his list of objects. His notations of this initial observation are interesting because they reveal the visible extent of M31 using primitive instruments under black-sky conditions:

"The beautiful nebula of the belt of Andromeda, shaped like a spindle; M. Messier has investigated it with different instruments, & he didn't recognize a star: it resembles two cones or pyramids of light, opposed at their bases, the axes of which are in direction NW-SE; the two points of light or the apices are about 40 arc minutes apart; the common base of the pyramids is about 15'.”

Also interesting is a hand-written annotation that Messier later added to his own copy of the printed catalog, because it tells us something more about the instruments he used:

“I have employed different instruments, especially an excellent Gregorian telescope of 30 feet FL, the large mirror 6 inches in diameter, magnification 104x. The center of this nebula appears fairly clear in this instrument without any stars appearing. The light gradually diminishes until it becomes extinguished. The former measurements were made with a Newtonian telescope of 4.5 feet FL, provided with a silk thread micrometer.”

To reach 104X in his 6” f/60 reflector, Messier must have used an 88mm focal length eyepiece. Actually, that’s deceptive, because back then few telescopes had interchangeable eyepieces. In those days, if you needed a different power or field of view, you bought another telescope. Incidentally, although a 6” reflector may sound like an impressive instrument, reflectors back then used speculum metal, which even when new is much less reflective than today’s aluminum or silver coatings, and tarnishes very quickly. A 6” speculum-metal scope is about the equivalent of a 3.5” or 4” reflector nowadays.

From a dark-sky site like the Parkway, Andromeda is easy to spot naked eye. From a light-polluted site like Bullington, Andromeda can be hard to find if you’ve never found it before. Once you do find it, though, you’ll never have any problem finding it again. The Astronomical League rates M31 “Easy” with 7X50 binoculars, although they rate M32 a “Challenge” and M110 as not visible. To find M31 with binoculars, the first step is to find Mirach, which is beta-Andromedae, the second brightest star in the constellation Andromeda. To do that, let’s go back to the chart I had up a moment ago.

050: Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Perseus, Triangulum Overview

You should be able to locate Cassiopeia easily. Shedir, at magnitude 2.23 the brightest star in Cassiopeia, is at the bottom right of the “W” or the top left of the “M”, depending on how you look at it. The triangle of which Shedir forms the apex points directly at Mirach (magnitude 2.06) in Andromeda. The two are separated by about 21.5 degrees, or about two fists held at arm’s length. There is no other star even remotely as bright as Mirach in that vicinity. You can verify you have the right star by looking for a clear isosceles triangle formed by the three brightest stars in the area, all of which are second magnitude. Shedir in Cassiopeia forms the apex, with Mirach and Almaak in Andromeda forming the base. Once you’ve located Mirach, finding M31 is easy in binoculars.

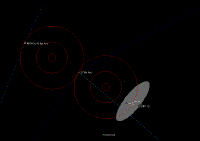

060: Andromeda with Binoculars

The circles on this chart are 7 degrees, which matches our 7X50 binoculars. Most other 7X to 10X binoculars have 6 to 8 degree fields, so the view should be similar in your binocular. Put Mirach on the edge of the field, with most of the field skewed towards Cassiopeia and slightly away from Almaak. How much isn’t critical. Near the center of your field, you’ll see 37 Mu Andromedae. At magnitude 3.9, it’s by far the brightest star in the field other than Mirach. On the line formed by Mirach and 37 Mu Andromedae, swing your binoculars about half a field away from Mirach, until 37 Mu Andromedae is just on the edge of the field. M31 should be about centered in your view. M110 won’t be visible in your binocular. With averted vision, M32 may be marginally visible as a bright knot on the edge of M31.

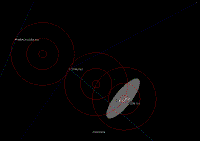

Once you’ve found M31 with binoculars, it’s not hard to find it with your scope.070: Andromeda with Telrad

To begin, point your Telrad so that Mirach is on one edge of the 4 degree circle and 37 Mu Andromedae on the other. Pivot your scope on the line formed by those two stars to put 37 Mu Andromedae on the far edge.

080: Andromeda with Telrad

Once you have 37 Mu Andromedae on the edge, continue on the same line half a Telrad field. M31 should be about centered in your optical finder. If you’re using a low-power eyepiece, M31 should also be about centered in the eyepiece.

In your main scope, M31 should be visible as a moderately bright central gray fuzzy, surrounded by darker gray fuzz. Depending on how wide your field of view is, you may need to pan around a bit to find M32 and M110, but you should be able to get all three in one field of view if your eyepiece gives you at least one and a third degrees or so. M32 will be visible as a brighter knot on the edge of the M31 nebulosity. M110 will be visible as a dimmer patch with a distinct oval form to the opposite side of M31.

Regardless of the size of your scope, you’ll be able to see more detail if you use averted vision. Time constraints mean I have to move along quickly, but I hope you’ll spend some time with the Andromeda galaxies. If you have a moderate to large scope, you can easily spend an hour or more on M31 alone, and still be discovering additional details.